It’s a classic hip-hop trope and a constant failure of society, that Black culture is so widely enjoyed and imitated, but rarely respected. So often do the biggest stars finally make it big after a life of strife and scraping, only to be lied to, taken advantage of, and squander that success without the proper support and education. Think how many star athletes and flash in the pan rappers go broke. Goyard Ibn Said, the debut album from radical Philly MC and producer Ghais Guevara, is a fully realized exploration of this tragedy in his own life, the culture at large, and its historic context.

Framed as a literal stage play (emphasis on tragedy) and chronicling the titular persona’s rise and fall in the rap industry, Goyard Ibn Said begins with his spoils of success in frivolity, women, and addiction, only for a gradual shift as he becomes aware of the exploitation and impurity to which he’s been subjected. Not only does one enjoy these spiritual poisons, but they also become accustomed to them, losing sight of their humble, yet proud roots. At risk of sounding like a Redditor – it’s structurally and thematically not far off from To Pimp a Butterfly or plenty of Lupe Fiasco records, to whom Ghais is often compared.

Ghais’ own experiences as a hot young indie artist working on this major label debut are blown up to theatrical displays of debauchery, and later, an equally militant rejection. Where his previous work was rife with moral contradictions, Goyard Ibn Said is more explicitly split in order to show his emotional progression in life. Take early tracks like “Leprosy” or “Camera Shy“, tearing down the women in his life as sex objects or showering them in shallow compliments and material gifts, compared to the later “Critical Acclaim” which shows a more intimate, if contentious relationship; however, this could also be taken as the struggles between a young talent and his supposed team, and the fucking as a metaphorical rape, pimping, whatever you want to call it.

Imma write me a hit like I’m cookin the yay’ / Snatch a n—- up, hide the body in a trench like it ain’t no war in the Ba Sing Se

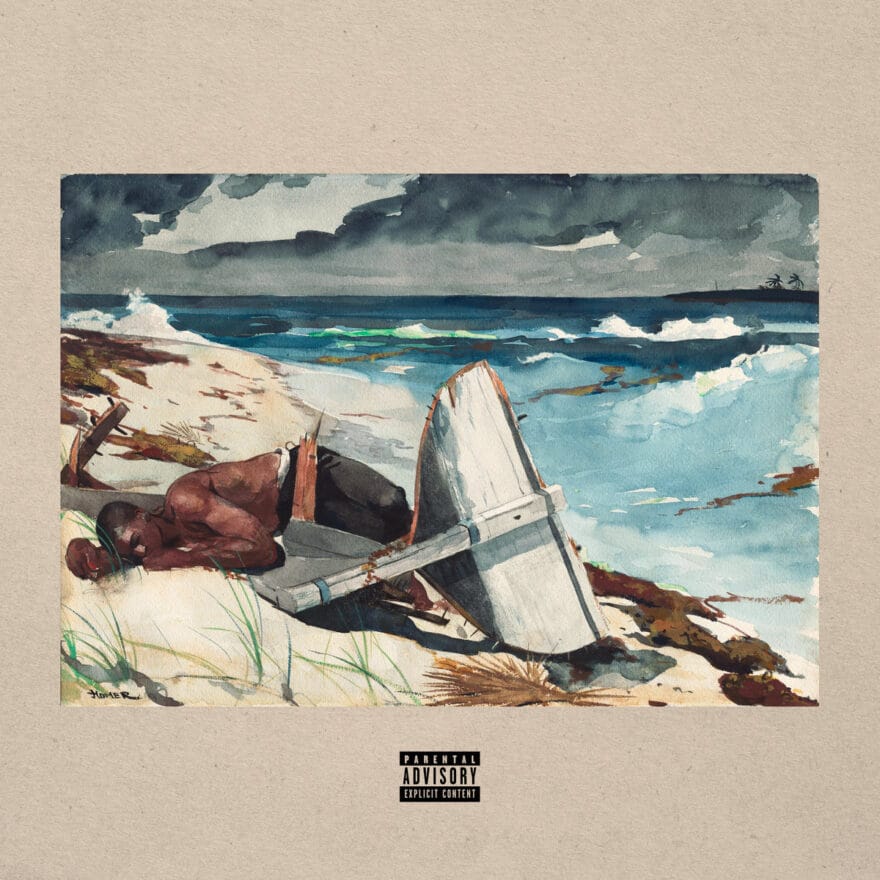

An additional perspective Ghais layers in is this power structure’s historic evolution; the fictional Goyard name being adopted from Omar Ibn Said, an 18th Century Muslim slave taken to America and supposedly a forced Christian convert. The very same Western indoctrination and erasure of proud, educated heritage takes place in a similar, if less physical fashion today. The slave trade’s reset of African culture set the stage for a character like Goyard, who falls for similar tricks and empty promises today and forgets the rich faith he could have otherwise held.

If Goyard’s ultimate rejection of sin lands him poor and alone, that may be a victory in itself. If Omar were to be washed up and castaway, that may be a better fate than the vapid, corrupt status symbols White America could hold for him. The socialist sacrifice made by Ghais is not pretty, but is necessary to enact real change for everyone like him.

As far as the rapping itself goes, Ghais’ words hold more weight than most rappers’; not a bar is wasted and every one is delivered with absolute conviction, belief, and energy in what he says. He has a special ability to take typical hip-hop street talk and give it a global, sociopolitical scope. Goyard doesn’t fuck bitches, but rather, he’s “a Muslim n—- with a French bitch, Battle of Algiers”. He’s highly allegorical and encourages you to do the knowledge, piquing curiosity with every reference.

The production on Goyard Ibn Said is a far cry from the bombastic samples of 2022’s There Will Be No Super-Slave. It’s synthy and less in your face, so while it might be a disappointing first listen if that was your expectation, it does fit the concept and Ghais seems to have generally matured in this time. The prelude mixtape Goyard Comin’: Exordium implied this, with a more straightforward sound that platforms his rapping. Is the label at all responsible for this? He already pokes fun at Fat Possum in the album’s intro and it’s in line with Goyard’s own story, having an artistic vision compromised due to industry dollars. That’s as much as I’ll speculate on the relationship though.

Feature-wise, E L U C I D, while more esoteric, is an obvious match for Ghais given their shared affinity for the industrial and all things proudly revolutionary. McKinley Dixon also seems to have a great relationship with him, returning the favor for Ghais’ feature on Beloved! Paradise! Jazz!? with the album’s one stripped back jazz record. While they often fall on opposite sides of the spectrum tonally, their chemistry is natural. Further collabs would be more than welcome.

All things said, Goyard Ibn Said is a natural progression in Ghais Guevara’s career. The raised conceptual stakes and label budget have platformed his war on rap gentrification and materialism, an even greater accomplishment than the now-stacked discography he’s built. Despite what he might assert on the final song, if you care about hip-hop and an artists’ right to expression, you cannot skip this.

PS: Goyard please don’t call me a cracker, I just write for fun.